The relationship between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and Zimbabwe is a lasting anomaly. It stands out in the global geopolitical landscape. This alliance was born from anti-colonial solidarity during the Cold War. It evolved into a deeply personal partnership. It became a pragmatic collaboration between two autocratic regimes. Their connection is defined by ideological affinity. It is marked by infamous military cooperation. The regimes share a common interest in evading Western-led international norms and sanctions. This report examines how the relationship evolved, beginning with Pyongyang’s support for Robert Mugabe’s liberation struggle. It highlights the alliance’s surprising resilience in the post-Mugabe era. The bond is not merely a Cold War relic. It is a partnership deeply institutionalized within Zimbabwe’s military apparatus.

Foundations of the Alliance: Cold War and Liberation

The North Korea-Zimbabwe relationship was forged in the geopolitical context of the Cold War and African decolonization. During this era, Pyongyang’s foreign policy was driven by its fierce competition with South Korea for international legitimacy. North Korea strategically positioned itself as a champion of the Third World. It offered significant military and civil aid to radical African states and anti-colonial movements. This support was both ideological and pragmatic. It was designed to secure political loyalties. Additionally, it aimed to advance its own national interests on the world stage.

This strategy led to its involvement in the Rhodesian Bush War. Pyongyang actively supported Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU). It also supported its military wing, ZANLA. While the Soviet Union backed a rival faction, North Korea provided practical military training to ZANLA guerrillas. They trained them in hidden camps near Pyongyang. The training included the use of advanced weaponry and explosives. This early support created a deep political and emotional debt. When ZANU unexpectedly won the 1980 elections, North Korea was cemented as a key “war-time friend” of the new regime.

The core of the alliance was beyond strategic calculations. It was the powerful personal bond between Kim Il Sung and Robert Mugabe. It was also an ideological connection. As former guerrilla fighters turned autocratic leaders, they shared a common life experience that fostered mutual admiration and trust. Mugabe first visited Pyongyang in 1978 to seek military support. He deeply admired North Korea’s Juche ideology. He viewed it as a blueprint for post-colonial nations to achieve political and economic independence. This personal connection transformed a strategic alliance into a durable partnership.

The Darkest Chapter: The Gukurahundi Massacres

After Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980, the alliance entered its most notorious phase. To strengthen his power against internal rivals, Mugabe leveraged his close ties with Pyongyang. In October 1980, he signed a military agreement with Kim Il Sung for an “exchange of soldiers.” This agreement laid the groundwork. North Korea was set to train a new elite brigade for the Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA). In August 1981, 106 North Korean military advisors arrived. They began training this unit. It became known as the Fifth Brigade.

The Fifth Brigade was explicitly designed for internal repression. The Brigade was comprised almost entirely of ethnically Shona former ZANLA fighters. It operated outside the normal military chain of command. The Brigade answered directly to Mugabe. It had its own codes, uniforms, and equipment, effectively making it a private army for the ruling ZANU-PF party.

From 1983 to 1987, the Fifth Brigade was deployed to the Matabeleland and Midlands provinces—strongholds of the rival ZAPU party—in an operation Mugabe named “Gukurahundi” (the early rain which washes away the chaff). Under the pretext of quelling a dissident movement, the brigade unleashed a systematic campaign of terror against civilians, resulting in an estimated 20,000 deaths.

The operation was marked by extreme brutality, including public executions, mass torture, and systematic rape. North Korea’s role was fundamental; its advisors provided the specific training, discipline, and tactical blueprint for this highly effective instrument of political repression.

Bronze, Bullets, and Hard Currency

After the Cold War, the relationship transformed from one of military and ideological patronage to a pragmatic economic partnership. The key actor in this phase was Mansudae Overseas Projects (MOP). MOP is the international commercial arm of North Korea’s state-run art studio. MOP became a vital tool for the Kim regime to earn desperately needed hard currency. They exported artists and laborers to build large-scale monuments in the distinct North Korean socialist-realist style.

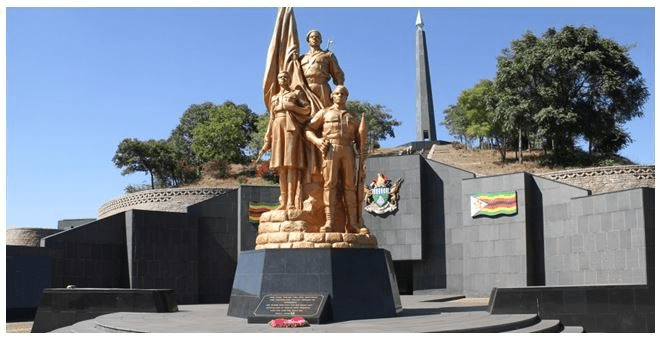

The most prominent example in Zimbabwe is the National Heroes’ Acre in Harare. It is a 57-acre national monument and burial ground. Its construction began in 1981. The design was led by North Korean architects. It explicitly mimics the Revolutionary Martyrs’ Cemetery in Pyongyang. This design serves as a powerful ideological instrument. It physically cements ZANU-PF’s liberation narrative into the national landscape.

This “monument diplomacy” extended to other projects. It included two large statues of Robert Mugabe commissioned for a total of $5 million. This provided a direct stream of foreign currency to the heavily sanctioned North Korean regime. These activities have drawn international scrutiny, with UN experts investigating Zimbabwe for potential sanctions violations.

An Enduring Partnership in the Modern Era

The alliance’s resilience is one of its most remarkable aspects. Both nations became increasingly isolated. North Korea faced isolation for its nuclear program. Zimbabwe was isolated due to human rights abuses. Their shared status as “pariah states” reinforced their bond. This created a sense of common cause in opposing a Western-dominated international order.

The 2017 ouster of Robert Mugabe and the rise of his longtime ally, Emmerson Mnangagwa, did not sever these ties. This continuity showed that the relationship was not merely personal to Mugabe. It was institutionalized within the ZANU-PF and military elite. Many in these groups, including Mnangagwa, have their own histories with North Korea dating back to the Gukurahundi era.

A clear signal of this continuity came in February 2018, just months after Mugabe’s removal. A high-level Zimbabwean military delegation made an official visit to Pyongyang. This raised concerns about violations of UN sanctions prohibiting military cooperation. The two nations continue to exchange formal diplomatic messages, reaffirming their wish to strengthen bilateral relations.

Conclusion

The North Korea-Zimbabwe relationship offers a compelling case study. This alliance has adapted through global geopolitical shifts. It has endured international isolation and leadership transitions. It changed from a partnership based on shared anti-imperialist ideology. The relationship is now a pragmatic alliance of survival. It is rooted in a common history and mutually reinforcing regime interests. There are deep institutional ties within Zimbabwe’s ruling party and military. These ties suggest resilience. Even though it is largely symbolic, this axis is to persist as a lasting legacy of its Cold War origins.

This text was compiled with the assistance of Deep Research Gemini.